Assumed vs. Deserved

At first thought, I assumed the term “flawed character” to be synonymous to “character.” However, after some consideration, this doesn’t seem to be valid in all cases. Example one: President Bartlet, aka Martin Sheen, in The West Wing, the “God figure” who was arguably worshipped by his fellow characters on the show. Much the same, example two: Dumbledore, the kind of grandfather we all wanted but never had. And lastly, George Feeny in Boy Meets World, our favorite childhood mentor and role model. These characters are not just “characters”, they are flawless characters. However, for the majority of character who are not flawless, I still believe there are fundamental differences between a character who has flaws and a flawed character. A flawed character has a certain characteristic, a flaw, about him/her that continually influences the character’s actions and decisions. Joss Whedon perfects the use of flawed characters in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, specifically in the two-part pilot, to champion the underdog, women, and introduce conflict.

At first, Buffy seems like your typical blonde, superficially pretty, run-of-the-mill high school teenager. Joss Whedon admits that this was exactly what he was going for. That blonde chick that always dies first in a horror film? Yeah… her… Initially, the audience assigns Buffy’s character flaw: a woman, she is a woman. Although she serves as the “superhero” of the series, it is assumed that she is weaker, less intelligent, and more emotional than a man. The fact that she is a woman will negatively affect how she handles situations and makes decisions. However, pretty soon the viewer realizes that Buffy isn’t the stereotypical dumb blonde but quite far from it. Within minutes, Buffy is shown, in Joss Whedon’s words, “kicking butt.” She kicks down Angel, kills countless vampires, and saves a concert hall full of students. During these scenes, the viewer is not focused on the fact that Buffy is a woman, but on the fact that Buffy is, in my words, kicking ass. Buffy’s assumed character flaw wasn’t a character flaw at all, but instead, an audience flaw.

Joss Whedon introduces a flawed character, Cordelia, to provoke conflict in the first two episodes of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Cordelia’s character flaw is, at first, hidden from the viewer as she generously offers her book to Buffy. Nevertheless, Cordelia’s true colors are revealed as she spews bitchy, for lack of a better word, comments about fashion and requirements to be popular. Her character flaw? Cattiness. After Buffy pins Cordelia against a wall, and saves all the students from hungry vampires which Cordelia conveniently forgets, Cordelia is heard gossiping about Buffy. Although the conflict of savage vampires is already incredibly relevant in the series, the conflict between Buffy and Cordelia supported by Cordelia’s cattiness is more relatable to the viewers. Joss Whedon’s use of a flawed character allows the audience to feel more connected to the story.

Although there are no George Feeny’s or President Bartlet’s, Buffy the Vampire Slayer displays a variety of characters with assumed character flaws and deserved character flaws. Let’s all just remember what people say about those who make assumptions…

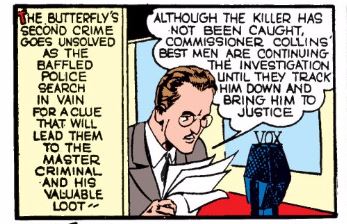

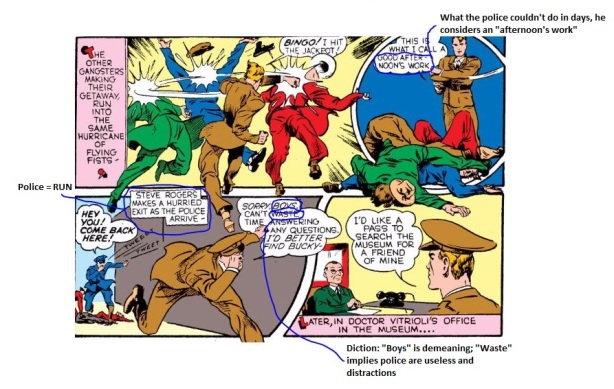

beginning of “The Queer Case of the Murdering Butterfly and the Ancient Mummies”, the police visit Doctor Vitrioli after the notorious killer, The Butterfly, threatens to steal treasure from the doctor’s museum. After The Butterfly easily kills two night guards and steals the precious jewels, the radio announcer ensures that the commissioner has his “best men” on the job, although his best have been completely unsuccessful and are extremely “baffled.” Bucky soon after visits the museum and conveniently stumbles upon The Butterfly’s lair, which one would think the police could have found by now if a squirmy boy found it within a few minutes. Meanwhile, The Butterfly has enlisted several crooks to rob a bank although immediately and coincidentally confronted by Steve Rodger

beginning of “The Queer Case of the Murdering Butterfly and the Ancient Mummies”, the police visit Doctor Vitrioli after the notorious killer, The Butterfly, threatens to steal treasure from the doctor’s museum. After The Butterfly easily kills two night guards and steals the precious jewels, the radio announcer ensures that the commissioner has his “best men” on the job, although his best have been completely unsuccessful and are extremely “baffled.” Bucky soon after visits the museum and conveniently stumbles upon The Butterfly’s lair, which one would think the police could have found by now if a squirmy boy found it within a few minutes. Meanwhile, The Butterfly has enlisted several crooks to rob a bank although immediately and coincidentally confronted by Steve Rodger s strolling by. Rodgers beats up the gangsters, just a “good afternoon’s work” for him, but flees the scene when the police arrive seconds too late. Skipping ahead a few scenes, Captain America defeats The Butterfly and discovers the villain’s true identity, Doctor Vitrioli. Always two steps behind Captain America, the police rush in only for Captain America to once again flee the scene and the cops. The ending sequence shows Steve Rodgers and Bucky reading the newspaper as it congratulates the police for a job well done in catching The Butterfly.

s strolling by. Rodgers beats up the gangsters, just a “good afternoon’s work” for him, but flees the scene when the police arrive seconds too late. Skipping ahead a few scenes, Captain America defeats The Butterfly and discovers the villain’s true identity, Doctor Vitrioli. Always two steps behind Captain America, the police rush in only for Captain America to once again flee the scene and the cops. The ending sequence shows Steve Rodgers and Bucky reading the newspaper as it congratulates the police for a job well done in catching The Butterfly. sponsibility, which is really just an “afternoon’s work” for him anyway. The police become like a nagging mother or annoying fly that Captain America must shake although the police will eventually and inevitably receive all the glory. The concept inspires a deeper issue explained by Fredric Wertham, “ [A hero]… undermines the authority and the dignity of the ordinary man and woman in the minds of children.” And in this case, the ordinary man and woman are the police. If comics imply that there are justifiable situations in which a “hero” must run away and avoid the police, whether due to the police’s competence or another reason, they are creating a fine line between good Samaritans and radical anarchists.

sponsibility, which is really just an “afternoon’s work” for him anyway. The police become like a nagging mother or annoying fly that Captain America must shake although the police will eventually and inevitably receive all the glory. The concept inspires a deeper issue explained by Fredric Wertham, “ [A hero]… undermines the authority and the dignity of the ordinary man and woman in the minds of children.” And in this case, the ordinary man and woman are the police. If comics imply that there are justifiable situations in which a “hero” must run away and avoid the police, whether due to the police’s competence or another reason, they are creating a fine line between good Samaritans and radical anarchists.