F* the Po-Po?

When thinking of Captain America, one most likely reflects on his courage, loyalty, and passion for justice. His honor resides in defeating evil so that good can prevail. Although perhaps reductive, this mentality is also shared by the police (minus the cape and body suit to accompany it.) The police force was created to enforce laws that promote justice and peace. To assume that Captain America and the police are companions or allies would not be foolish. However, all too often in the comics, Captain America’s agenda seems to conflict with the police’s agenda. Captain America and the police may desire the same outcome, but the strategies of the two do not seem to align. To take the argument further, this misalignment creates barrier between the two such that the story becomes the police vs. Captain America vs. the criminals. For children reading Captain America Comics, the fact that Captain America and the police are not allies must mean that either a) there are situations where good people and the police are at odds or b) the police are bad. This idea is specifically apparent in Captain America Comics, “The Queer Case of the Murdering Butterfly and the Ancient Mummies” where the police are so inept that they become annoying obstacles for Captain America to avoid.

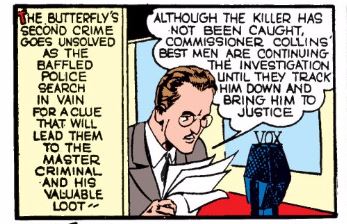

In the  beginning of “The Queer Case of the Murdering Butterfly and the Ancient Mummies”, the police visit Doctor Vitrioli after the notorious killer, The Butterfly, threatens to steal treasure from the doctor’s museum. After The Butterfly easily kills two night guards and steals the precious jewels, the radio announcer ensures that the commissioner has his “best men” on the job, although his best have been completely unsuccessful and are extremely “baffled.” Bucky soon after visits the museum and conveniently stumbles upon The Butterfly’s lair, which one would think the police could have found by now if a squirmy boy found it within a few minutes. Meanwhile, The Butterfly has enlisted several crooks to rob a bank although immediately and coincidentally confronted by Steve Rodger

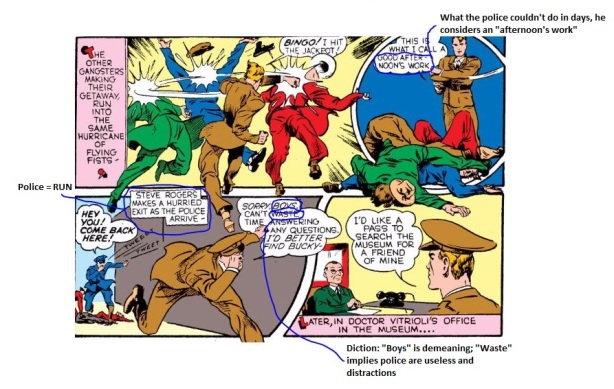

beginning of “The Queer Case of the Murdering Butterfly and the Ancient Mummies”, the police visit Doctor Vitrioli after the notorious killer, The Butterfly, threatens to steal treasure from the doctor’s museum. After The Butterfly easily kills two night guards and steals the precious jewels, the radio announcer ensures that the commissioner has his “best men” on the job, although his best have been completely unsuccessful and are extremely “baffled.” Bucky soon after visits the museum and conveniently stumbles upon The Butterfly’s lair, which one would think the police could have found by now if a squirmy boy found it within a few minutes. Meanwhile, The Butterfly has enlisted several crooks to rob a bank although immediately and coincidentally confronted by Steve Rodger s strolling by. Rodgers beats up the gangsters, just a “good afternoon’s work” for him, but flees the scene when the police arrive seconds too late. Skipping ahead a few scenes, Captain America defeats The Butterfly and discovers the villain’s true identity, Doctor Vitrioli. Always two steps behind Captain America, the police rush in only for Captain America to once again flee the scene and the cops. The ending sequence shows Steve Rodgers and Bucky reading the newspaper as it congratulates the police for a job well done in catching The Butterfly.

s strolling by. Rodgers beats up the gangsters, just a “good afternoon’s work” for him, but flees the scene when the police arrive seconds too late. Skipping ahead a few scenes, Captain America defeats The Butterfly and discovers the villain’s true identity, Doctor Vitrioli. Always two steps behind Captain America, the police rush in only for Captain America to once again flee the scene and the cops. The ending sequence shows Steve Rodgers and Bucky reading the newspaper as it congratulates the police for a job well done in catching The Butterfly.

Now, just to sum up the story in a few words: police cannot find villain, little sidekick boy effortlessly finds villain, Captain America defeats crooks, police are too late, Captain America defeats villain, police are too late, police get credit for defeating villain. The takeaway from this story is incredibly obvious, the police (“boys”) are too incompetent (“baffled”) to promote and administer justice so Captain America must take on re sponsibility, which is really just an “afternoon’s work” for him anyway. The police become like a nagging mother or annoying fly that Captain America must shake although the police will eventually and inevitably receive all the glory. The concept inspires a deeper issue explained by Fredric Wertham, “ [A hero]… undermines the authority and the dignity of the ordinary man and woman in the minds of children.” And in this case, the ordinary man and woman are the police. If comics imply that there are justifiable situations in which a “hero” must run away and avoid the police, whether due to the police’s competence or another reason, they are creating a fine line between good Samaritans and radical anarchists.

sponsibility, which is really just an “afternoon’s work” for him anyway. The police become like a nagging mother or annoying fly that Captain America must shake although the police will eventually and inevitably receive all the glory. The concept inspires a deeper issue explained by Fredric Wertham, “ [A hero]… undermines the authority and the dignity of the ordinary man and woman in the minds of children.” And in this case, the ordinary man and woman are the police. If comics imply that there are justifiable situations in which a “hero” must run away and avoid the police, whether due to the police’s competence or another reason, they are creating a fine line between good Samaritans and radical anarchists.